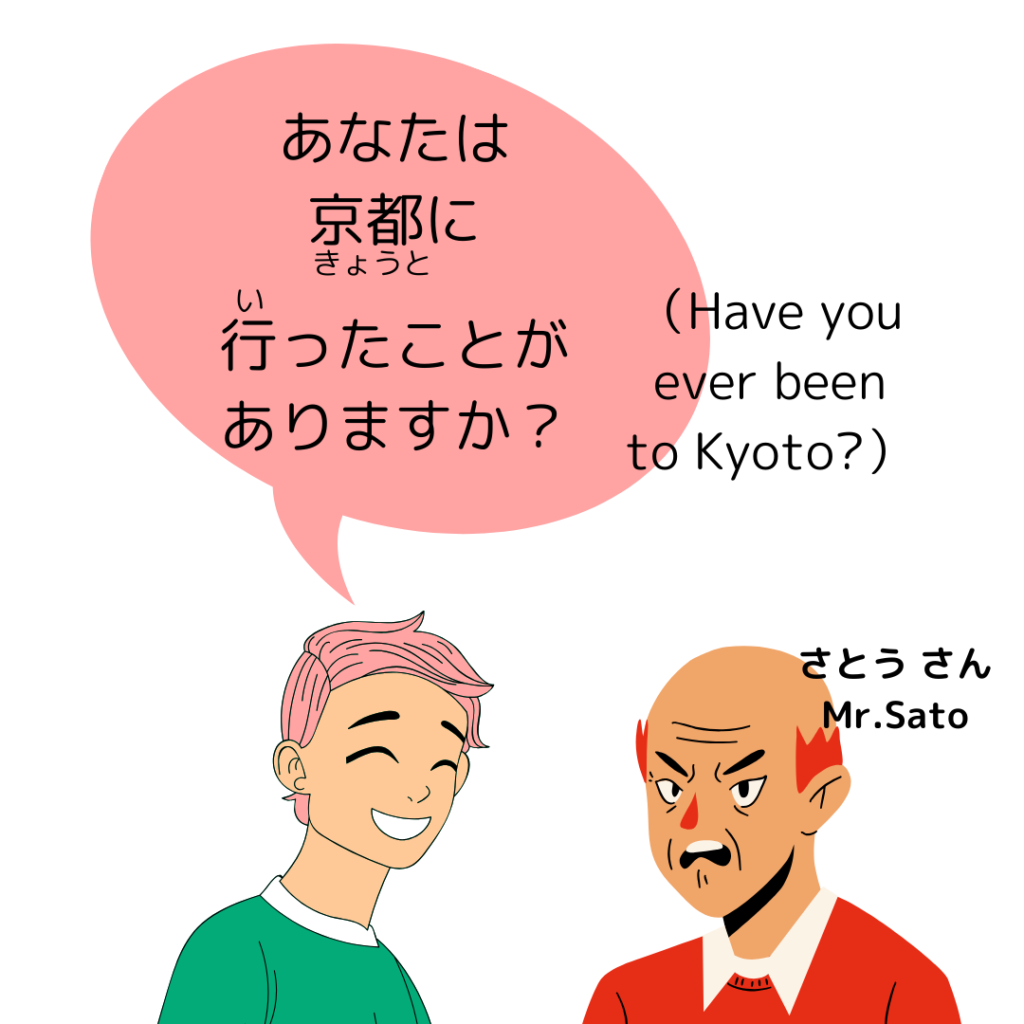

下の絵(え)を見てください。

佐藤(さとう)さんは、怒(おこ)っているようです。

どうして怒っているか、分(わ)かりますか?

この記事(きじ)を読(よ)めば、どうして佐藤さんが怒っているのか、分かります。ポイントは、「あなた」の是非(ぜひ)です。

Please look at the picture ↑. Mr. Sato on the right appears to be angry. Do you know why he is angry? You will find out by reading this article. The point is whether to use the word ”あなた” or not.

「あなた」は失礼(しつれい)!

日本語では、話し相手(はなしあいて)に「あなた」と言うことは、少(すく)ないです。特(とく)に話し相手(はなしあいて)が自分より年上(としうえ)や目上(めうえ)なら、「あなた」と言(い)うことは、ほどんどありません。

「あなた」と言うと、失礼(しつれい)な感じ(かんじ)がするからです。

同(おな)じ年齢(ねんれい)の人、立場(たちば)が下(した)や年下(としした)の人になら、言ってもいいです。ただし、ちょっと相手(あいて)が「ん?」という戸惑い(とまどい)を見せるかもしれません。

この絵では、明(あき)らかに、さとうさんの方が年上です。だから、さとうさんは怒っているのです。

In Japanese, it is rare to use ‘anata’ (あなた:you) when calling someone. Especially if the person you are talking to is older or of higher status, you almost never use ‘anata’. This is because it can sound rude. It is okay to use ‘anata’ when talking to someone of the same age, lower position or younger to you. However, the other person may show some confusion. In this picture, it is clear that Mr.Sato(さとうさん) is older. That’s why Mr.Sato is angry.

じゃあ、どう呼(よ)ぶの?

日本人は「あなた」ではなく、名前(なまえ)を呼(よ)びます。

もし、さとうさんが近所(きんじょ)の人なら、「さとうさん」(名字(みょうじ)に、「さん」をつける)。学校(がっこう)の先生(せんせい)や医者(いしゃ)なら「先生」(「さとう先生」のように名字(みょうじ)をつけてもOK)。会社(かいしゃ)の上司(じょうし)なら「社長(しゃちょう)」「部長(ぶちょう)」のように、肩書(かたがき)で呼ぶのが普通(ふつう)です。

Japanese people call each other by their name instead of using ‘anata’. For example, if Mr.Sato is a neighbor, it’s normal to call him ‘Sato-san‘ (put ‘san’ after the family name). If Mr.Sato is a teacher or a doctor, it’s normal to call him ‘sensei’ (or ‘Sato-sensei‘:adding ‘sensei’ after the family name). If Mr.Sato is a boss at work, it’s common to call him as ‘Shacho’ (president) or ‘Buchou’ (department head) instead of using his name.

この絵のすずきさんは、怒っていません。

Mr.Suzuki in this picture is not angry.

意味(いみ)が変化(へんか)した二人称(ににんしょう)

昔(むかし)、「あなた」は「遠(とお)い所(ところ)」という意味(いみ)を表(あらわ)す言葉(ことば)でした。それが、いつしか、そこにいる人を表す言葉に変化(へんか)しました。直接(ちょくせつ)名前を呼ぶのは失礼(しすれい)だという考え方(かんがえかた)によるものです。つまり、そのころは「あなた」は敬称(けいしょう)だったと考(かんが)えられます。

ところが、それが少(すこ)しずつ、現代(げんだい)のような使われ方(つかわれかた)に変化しました。理由(りゆう)は、はっきり分かりませんが。

同(おな)じように、「お前(まえ)」・「貴様(きさま)」という二人称(ににんしょう)も、元々(もともと)は敬称でしたが、今は真逆(まぎゃく)のニュアンスで使います。

「お前」は友人(ゆうじん)や親(した)しい間柄(あいだがら)での二人称として使うこともありますが、ぞんざいな響(ひび)きの言葉です。年上や目上の人には絶対(ぜったい)に使いません。

「貴様」は、けんかをしている時(とき)などに、相手(あいて)を侮辱的(ぶじょくてき)に呼ぶ言い方です。

言葉は、長(なが)い時間(じかん)をかけて、意味が真逆に変化することもあるようです。おもしろいですね。

In the past, “anata” meant “a distant place” in Japanese. However, it gradually changed to mean “the person who is there”. This was due to the idea that it was impolite to call someone by their name. Therefore, it is believed that “anata” was an honorific title at that time.

However, it gradually changed to mean ‘you’ in modern times, though the reason for this is not clear.

Similarly, the second-person pronouns “omae(お前)” and “kisama(貴様)” were originally honorific titles, but now they are used in the opposite sense.

“Omae” can be used as a second-person pronoun between friends or people who are close, but it has a rough tone. It should never be used for people who are older or of higher position.

“Kisama” is a way of calling someone insultingly when you are fighting.

It seems that words can change their meanings in the opposite direction over a long period of time. It’s interesting, isn’t it?

結論(けつろん):「あなた」には気(き)を付(つ)けよう!

「あなた」と言う言葉には、気(き)を付(つ)けましょう。

日本語では、誰(だれ)と話しているかが明(あき)らかな場合(ばあい)、主語(しゅご)を省略(しょうりゃく)できます。

ですから、二人(ふたり)で話しているなら「YOU」に当(あ)たる言葉は、言わなくてもいいと思います。下の表(ひょう)のように。

Be careful with the word ‘あなた’. In Japanese, when it is clear who you are talking to, you can omit the subject. Therefore, if you are talking to each other, I think you don’t need to say the word that corresponds to “YOU”. As the table below.

| English(include ‘you‘) | Japanese | politer |

|---|---|---|

| What is your name? | 名前(なまえ)は? | お名前は? |

| How old are you? | いくつですか? | おいくつですか? |

| Where are you from? | どこから来(き)ましたか? | どちらからいらっしゃいましたか? |

表の右(みぎ)は、丁寧(ていねい)な表現(ひょうげん)です。

The right column of the table is a polite expression.

コメント